ARCHSTORMING | NEPAL SCHOOL PROJECT DESIGN COMPETITION

Team: Ar. Dristi Manandhar, Ar. Bibek Bhittrikoti, Ar. Pratima Basyal, Nimesh Maharjan, Pratik Shrestha

According to UNESCO and Nepal’s Ministry of Education, the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake damaged over 9,000 school buildings, disrupting education for nearly one million students. More recently, the monsoon floods of 2024 damaged at least 54 schools, affecting over 11,000 children, according to government and media reports. We continue to witness how public schools across rural Nepal face challenges that go far beyond education. In flood-prone and earthquake-prone regions, schools are more than just places of learning; they are lifelines, not just for students and teachers but also for the entire community. Yet many collapse during earthquakes, flood during monsoons, or deteriorate prematurely due to poor planning and substandard materials. These problems aren’t just about building infrastructures; they interrupt regular classes, drain community resources, and deepen educational disparity.

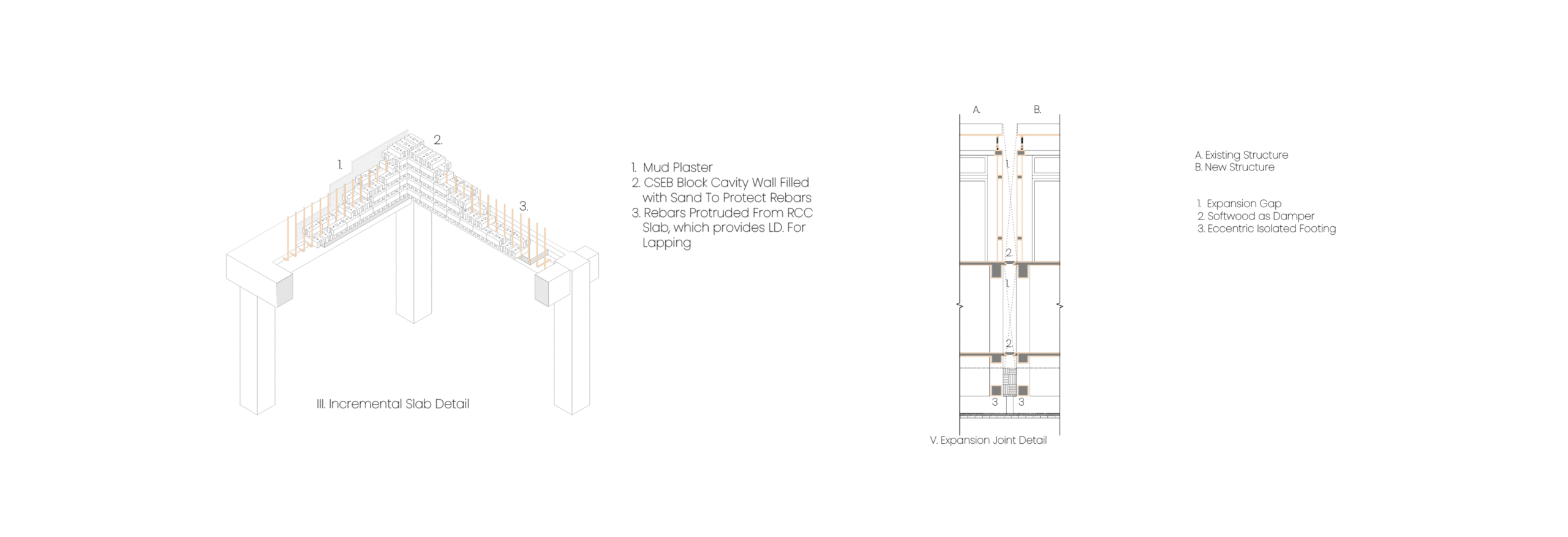

As a group of young architects working closely with these realities, we recognized the urgent need for a new kind of school prototype, one that is resilient, adaptable, affordable, while being deeply rooted in Nepal’s diverse local and cultural contexts. Therefore, our idea; A School that Grows, is inspired by how a tree lives. It starts small, takes root, and grows with its surroundings. Like branches reaching out, the school expands over time, shaped by the land, the climate, and the needs of its community. It grows strong, not all at once, but steadily, just like a tree.

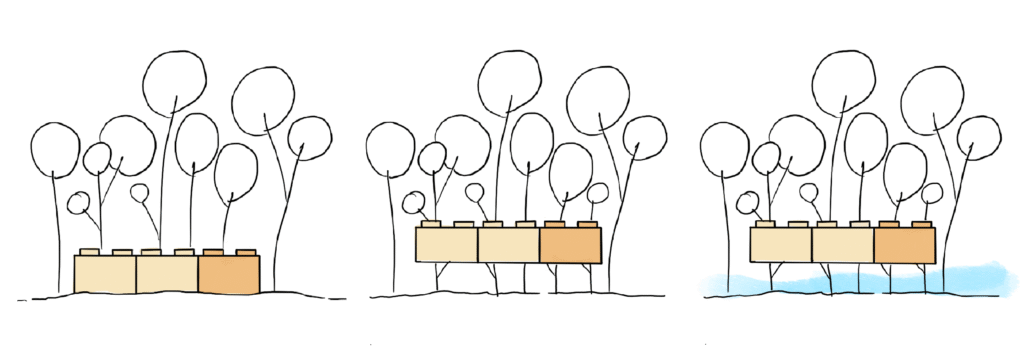

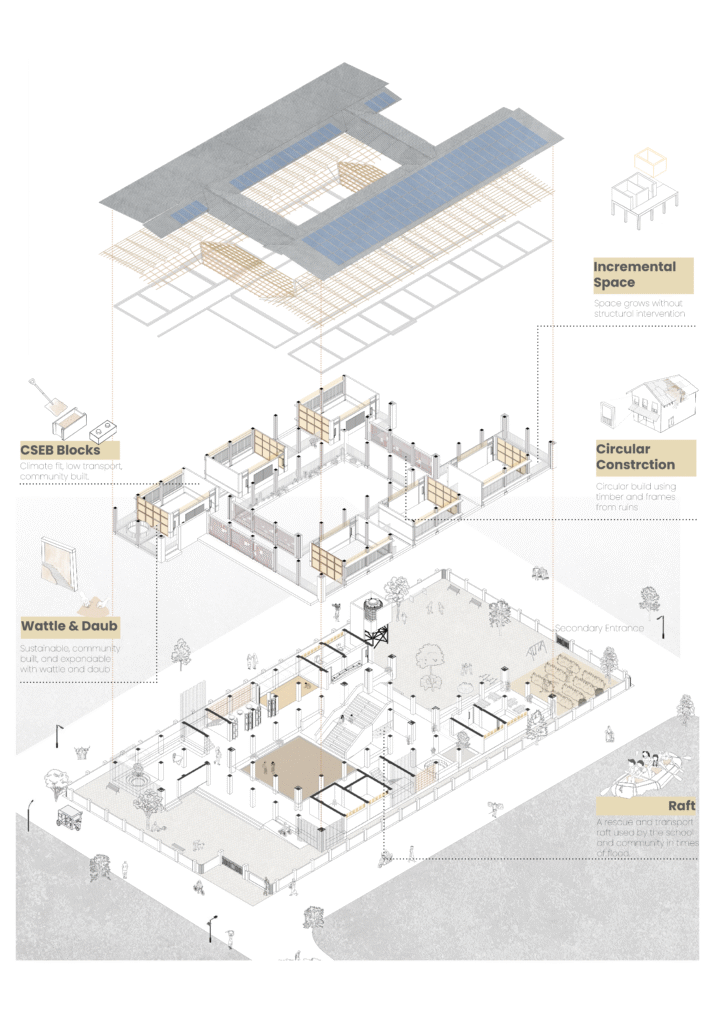

This concept isn’t just metaphorical. It forms the basis of a modular school system that can be built incrementally, adapted to varying climates just like a tree, and constructed using a blend of local materials, traditional building methods, and earthquake-resilient structures. So, for that we took a grid of 3.6 x 3.6-meter square grid, a size compatible with common materials like timber and concrete, and easy for local masons to construct. This dimension also aligns with spatial requirements outlined in Nepal’s Building Code (NBC). A 2×2 module (7.2m x 7.2m) forms a standard 35 sqm classroom with a corridor, meeting NBC guidelines, while a 1×2 grid fits programmatic needs like staircases or restrooms. This modular approach offers clarity, flexibility and ease for phased construction, which is quite common in the context of Nepal’s public schools. It means the school doesn’t have to be built all at once but can grow gradually as resources and needs evolve.

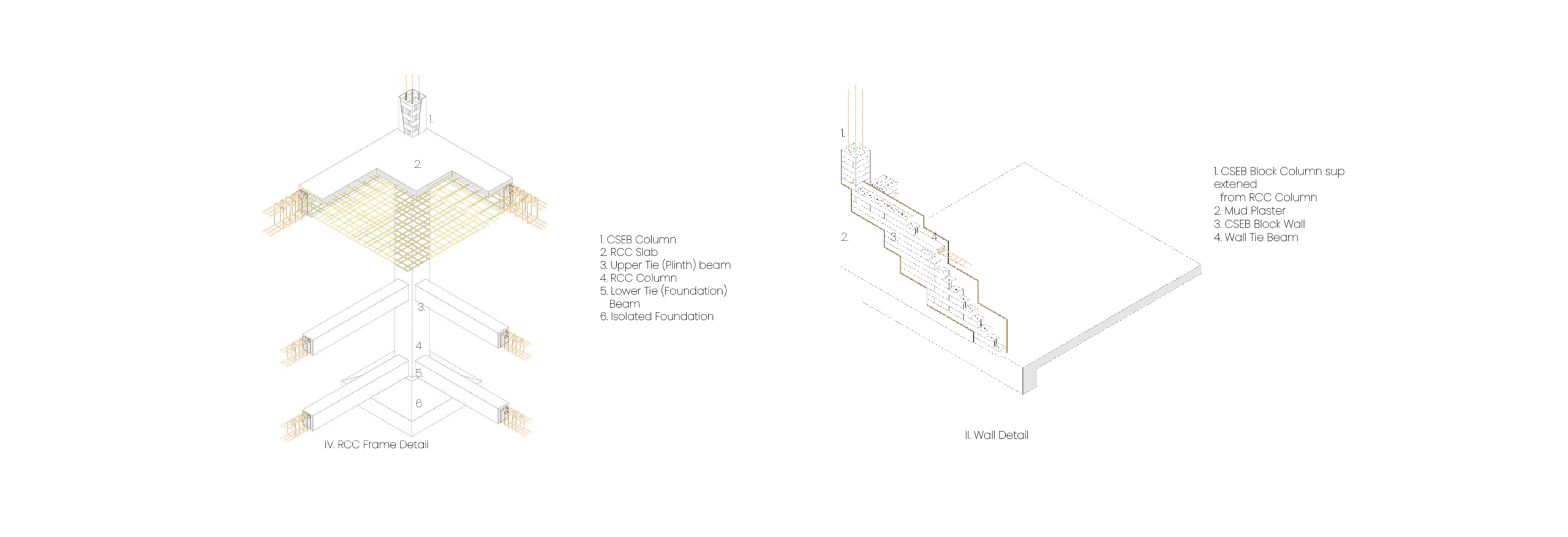

Choosing the right construction method was equally important to us, not just for safety but also to empower the local community to actively build and maintain their school. That’s why we proposed a hybrid system combining modern engineering with traditional techniques. Nepal’s National Building Code requires schools to be earthquake-resistant, and reinforced cement concrete (RCC) is widely trusted by local authorities in rural areas for its strength and durability. RCC also performs well in flood-prone zones, providing a robust foundation and vertical support that can withstand water damage.

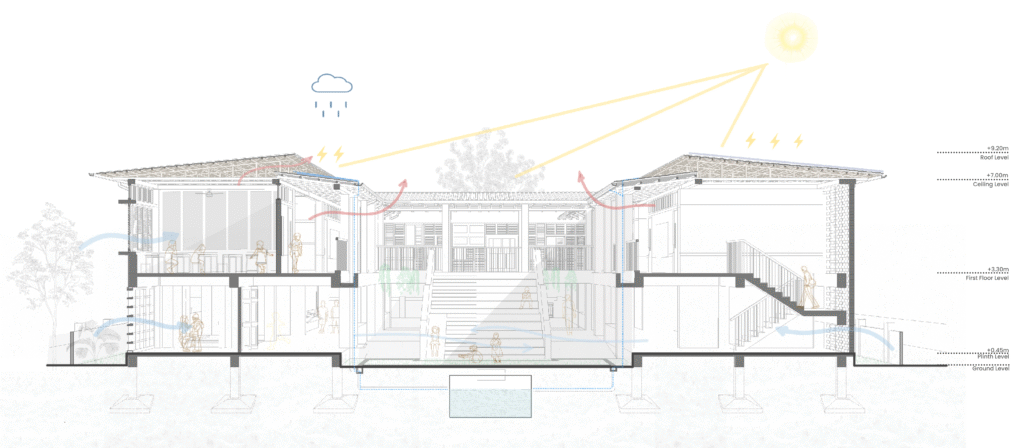

From an architectural standpoint, this hybrid approach allows us to meet stringent safety standards while reducing the building’s overall weight and environmental impact. We designed the foundations and columns with RCC for structural stability and flood resilience, while using lighter, locally sourced materials like compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEB), wattle and daub, or timber for the upper walls. These materials are not only more sustainable but also better suited to regional climates, allowing the building to breathe and adapt naturally to its environment.

As part of circular construction strategies, the design incorporates reused timber frames from disaster damage to ensure affordability, and community participation. Sustainability is further achieved through cross ventilation, stack effect, solar panels, rainwater harvesting used for flushing, cleaning, and irrigation, and false thatch ceilings for insulation. The courtyard doubles as an emergency space, with raft boats stored for flood resilience.

Too often, architecture in Nepal is a response to crisis. We wait for the next disaster before we act. But schools, especially in vulnerable areas, need to be prepared, not just repaired. This proposal is an invitation to think differently. To imagine schools that are more than shelters. That are alive, responsive, and truly part of their environment.

We hope that this prototype becomes a catalyst for broader discussion among policymakers, NGOs, and local governments on how we build smarter, safer, and with our people, not just for them.

Article by: Pratima Basyal